Every Single Street: The Running Project of a Lunatic or Highly Motivating Gamification?

Have you ever encountered that sudden feeling that your typical running route suddenly felt super boring?

Familiarity and routine have a lot going for them, of course. Our standard running routes require no thinking. We know exactly where it’ll go, how long it will be, and how to best spread our energy expenditure in order to make it through.

But sometimes it’s just so boring, isn’t it?

You’re longing for some change. Running it the other way around, maybe? Or get absolutely crazy and try a new route?

At some point around 2017 or 2018, I met a guy who would play a big role in my life later on. I’ve mentioned him here many times, he’s become sort of a guide in my running life without actually wanting to. Michael Mankus. Among the countless weird running projects he did, one day an activity of his in my Strava feed stood out: The GPS plot showed lots of squiggly lines, all in a sort of ball inside one particular neighborhood. In the description, something along the lines of “every single street.”

Just from seeing that activity name it was of course obvious to me what he was doing there. So I asked him what his exact goal was and how far down the line he had ventured yet. When he explained, my reaction wasn’t dismissive but intrigued.

I love a crazy vanity project!

He told me about Rickey Gates’ project by the same name. I don’t know who did it first, but Rickey certainly gave it a big boost in popularity. The guy had successfully registered the domain everysinglestreet.com for his go at the city of San Francisco. He did the inner city, a total of 1,317 miles (2,119 km), in just 45 days. His sponsor Salomon made a video about it.

If you haven’t caught on yet, #EverySingleStreet means to run through every single street of a given area—most often a major city or the hometown of the person who does the project. There are no fixed rules to it and no prizes to win, it’s just a fun thing to do when you get bored of your usual route.

And it can become addictive, fast!

There are a few independent projects out there which have made it possible to measure progress. My favorite one is called CityStrides.com (referral link), that’s also the one Rickey used in San Francisco. It works worldwide. The tool was created and is maintained by one guy named James Chevalier and works like this: You connect your GPS watch or tracking app to it and it will pull in all your past activities and starts syncing new ones.

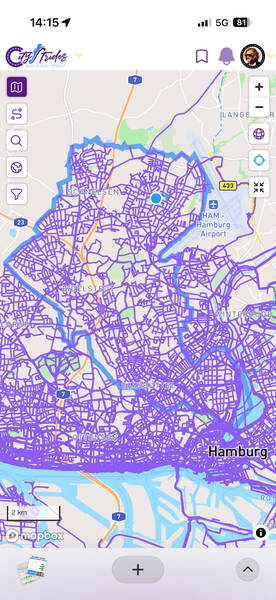

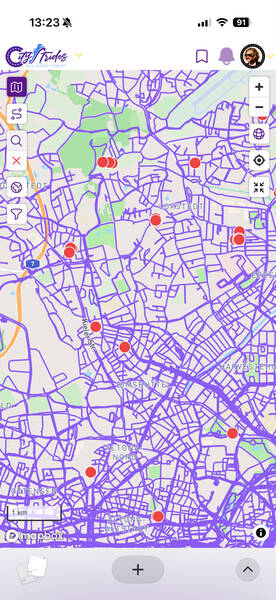

🗺️ This Creates Your Personal LifeMap

All your logged runs plotted on one single map of the world. For free! This alone is super cool. You get to zoom in on all the vacation runs you did, for example. A trip down memory lane!

With all the data, CityStrides can tell you how large of a percentage of certain cities and neighborhoods you have completed. And that, in turn, is used to create a ranking per city and neighborhood. The competitiveness aspect is not at the core of the tool, it feels more like a control center for your own progress. It celebrates you for reaching new milestones, but never compares you to others. This is refreshing and removes outside pressures.

I didn’t know about all this when I first saw Micha’s weird-looking Strava activities though. At the time, the project sounded fun to me but not like something I would immediately jump to do. It took a bunch of years until I met another guy who was into the project. Patrick Jeschak.

We first met at some point during the pandemic, and when planning a run together he told me that he’d love to take the train into my corner of Hamburg, because he was still missing quite a few streets around here. This led to a bunch of runs together through my neighborhood. And it didn’t take long until that process got me hooked.

The addictive powers of collecting something arbitrary were hard at work.

🙋 “Explain the Rules!”

Running all the streets of a city hasn’t started to be thing only when internet tools and GPS tracking became mainstream. Even Rickey Gates, while having his GPS watch log all the runs, planned it the old-school way by drawing his street collecting routes with a pencil onto printed maps and took those with him running through San Francisco. He used the then brand new CityStrides tool just to make sure to not be missing anything afterwards.

But I’m a numbers guy and very much into tech. So naturally I started right away by syncing all my runs to CityStrides and based all collecting efforts upon the ruleset of the platform. And that is as follows.

It’s all about the Nodes.

Not diving into the underlying technologies too much, but this much information is necessary so you can follow. In modern web-based mapping tools, streets are re-built by setting so-called Nodes—little GPS coordinate positions of significance to the streets’ features.

Imagine a street. It has a starting point and an ending point. Most often, those two points coincide with two points on other streets, where they meet. Those will be Nodes. Between the starting and ending points, the street might have a couple other streets joining it. Those are Nodes, too. And then, whenever the street changes direction, no matter how slightly, there’s another Node to translate the curvature. A short street in the middle of a residential area might have just a handful of Nodes, while a long major road can have hundreds.

The CityStrides rules state that in order to mark a street ‘completed,’ you need to have your uploaded GPS track come within 25 meters of 90% of its Nodes. Or, if you activate HARD MODE (as I obviously did), you’ll need to check the full 100% of all Nodes.

So far, so simple. There are a few edge-cases and little problems with this approach, but we’ll get to that later. Generally speaking, I think this is a good system.

CityStrides uses the mapping efforts of the crowd-created OpenStreetMaps, a project similar to Wikipedia from an organizational perspective. Lots of volunteers help improving the maps, and a bunch of experienced volunteer engineers help maintain quality.

The technology that then makes these maps easily viewable in the browser is sponsored by mapbox, a company that does a lot to do nonprofit support. CityStrides itself is for free, but offers a few helpful extra features for a low monthly fee I’m really happy to be paying to support this one-person project.

That’s all there is to know about how CityStrides works. You decide between default mode where 90% of a street’s Nodes will mark the street completed, and Hard Mode, where you’ll need 100% for it. Should you go for Hard Mode, your little avatar will get a badge so users will know that you’re basically working with a voluntary handicap here, but other than that there’s no difference.

📍 The Tricky Bit Is the Route Planning

While the LifeMap feature of CityStrides is hugely helpful in making missing streets visible, its route planning feature lacks ambition. It’s basically just like any other route planning tool, just without a full feature set. The first question you ask yourself when embarking on a street collecting run, is of course:

“How do I most efficiently cover the most streets in an area during a run of predefined distance?”

This is called the Chinese Postman Problem, or CPP for short. In order to cover every inch of all the streets in a given area without doing any bit twice, all junctions need to have an even-numbered amount of streets joining at them. So goes the theory. In the real world, this is almost never the case. So you then apply Dijkstra’s algorithm or a similar solution such as the Euclidian one in order to find the shortest possible connection. There are a few mathematicians and coders who have taken on this non-trivial problem and made their solutions public. I like the implementation by “solipsia” (here is a live demo) and the fork of that by clementh44 (here). The demo of “seen-one” is also neat.

Although street cleaners and actual postmen and women must have had solutions to the problem for ages, I wasn’t able to find out what measures they are usually taking.

The way I made most of my routes, though, was just by clicking them together manually in a route planner. It’s fast and easy to do, I rarely need more than 5-10 minutes for a 20 kilometer route. I use the built-in tool in Strava’s web interface, but they are all mostly the same. It doesn’t really matter which one you choose to use. The one on Strava also has a feature called “Personal Heatmap” that shows you all your logged runs of the past, the brighter the color the more often you’ve done the highlighted stretch. This is helpful, but I prefer the clarity of the CityStrides LifeMap next to my Strava route planner.

⌚ The Necessary Gear

It’s possible to just do this the old school way, map in hand, looking at the street signs all the time. Before getting really hooked on EverySingleStreet, I did a few navigated runs by holding my phone in my hand and looking at the route I had planned on a map on it. This was quite annoying, but it worked. The easiest solution is to get a GPS watch that has maps on it and can do navigation. It used to be these were quite expensive, and although I’ve been running a lot for many years, I never owned one of those. That is, until my favorite sports watch brand COROS came out with a wonderful watch at a fine price that would be capable of navigation: The COROS PACE Pro (not a sponsored link). It was available to buy starting in October of 2024, and that’s when I got really into collecting those streets.

Apart from the watch, the CityStrides subscription is a great investment in my opinion, as is a monthly ticket for public transit to get to the neighborhoods which aren’t as close by. You need your standard running gear, and that’s it.

🔬 What’s Street Collecting Like in Practical Terms?

In summer, I use my bike a lot to get to far-away areas quickly, as it’s often more efficient than the trains and buses in a packed city as Hamburg. The downside: hopping on the bike after a long-ish run, all sweaty, the winds at high speeds can increase the open window effect, making it tough for the immune system to not get dragged down. I sometimes took a spare set of dry clothes in my trail vest for the way back, but when it’s currently not the two warmest months of the year, it’s just not feeling right. More often than taking the bike, I therefore hopped into the train and traversed the city that way.

And for some very remote areas I took a car, and a few times, the ferry to cross the river. These runs turn into little adventures fast!

The travel times to and from the areas naturally increase over time. And I must say, this is the most annoying bit of the project for me. It’s just lots of dead time to be sitting on a train or in traffic. Cycling is best because it’s additional exercise, and a spin-down after the run feels great on the legs, but it’s not always practical.

📝 Route Planning Tactics and Route Length

The first few runs right around my home were of varying lengths, but the more I collected, requiring longer trips to the starting points, the longer my routes got. If I put in the effort to go somewhere, it should be worth it, was my thinking. The longest street collecting run I ever did so far was a 55 kilometer one in Schnelsen when preparing for the CCC ultra trail race in Chamonix, France. That way I fed two birds with one scone and ticked off a whopping 93 new full streets in just one go. That’s more than one full percentage point of Hamburg’s streets. It’s been an outlier, though—most often my runs were around the 20k distance, because I learned that this was my sweet spot. Just long enough to make some serious progress and justify the trip to and from the starting point, but not so long that I couldn’t continue with my usual training the next day.

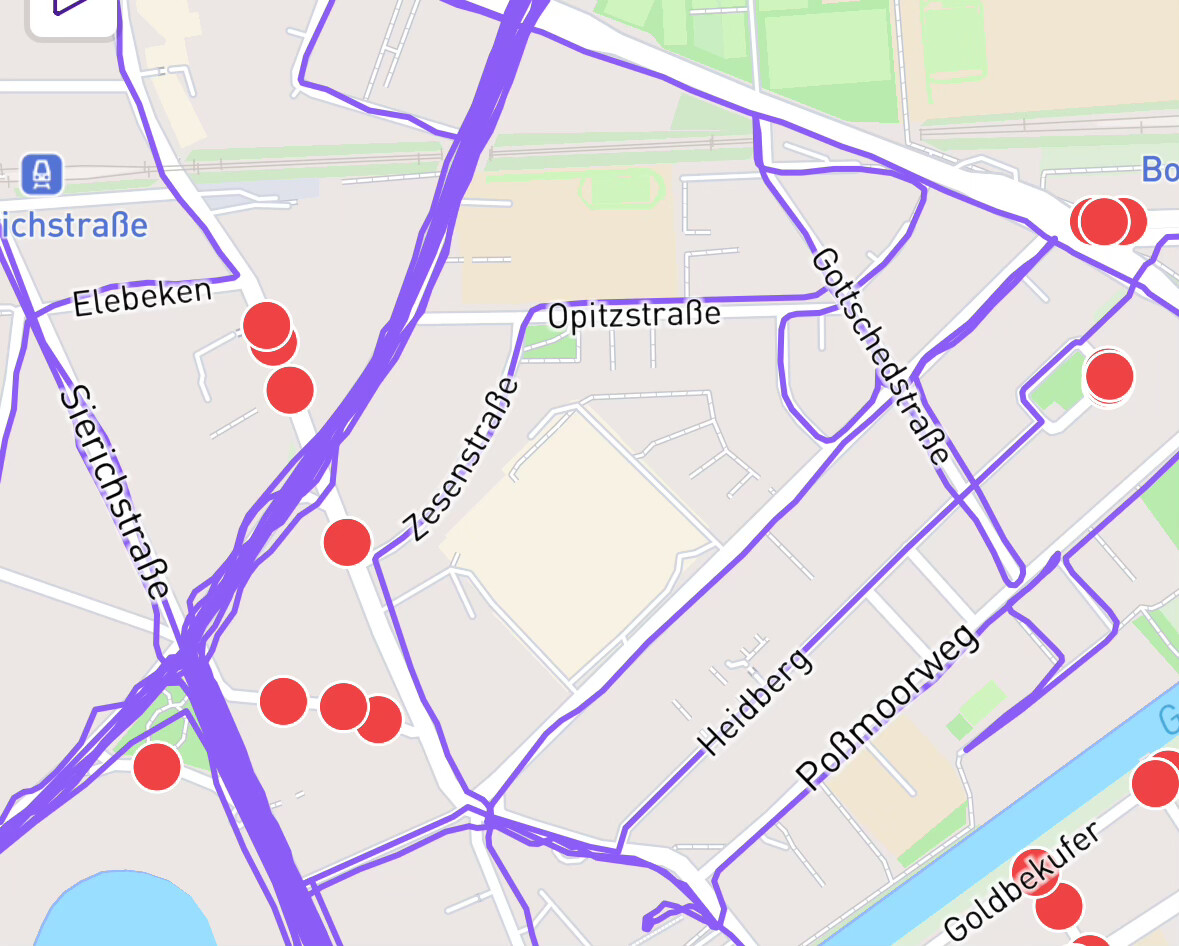

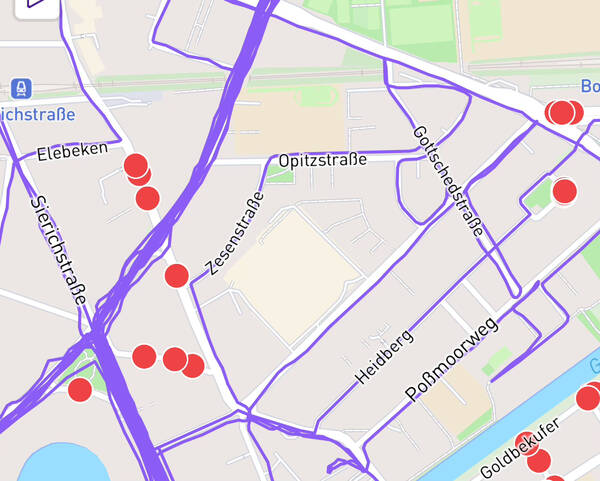

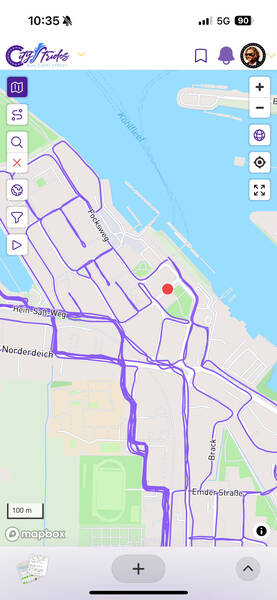

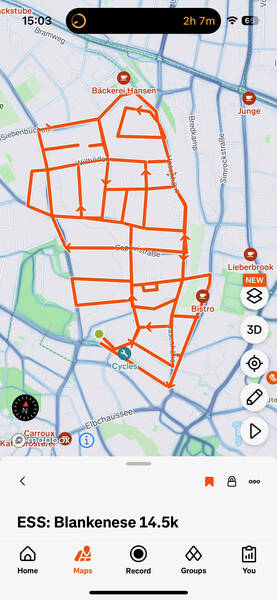

Regarding the route style, I have seen different approaches from other runners, but quickly landed on my own favorite one. I decide at which metro station I want to start and finish (most often the same one), and set a square-ish polygon next to it which I then try to fill out completely. Other people prefer zigzagging from A to B, or just going in a squiggly line on a big loop, but this type of planning is the most satisfying to me.

Taking a look at the tracking map afterwards looks great. And I can easily spot which little cul-de-sacs I’ve missed.

A fun side effect usually is that I get to meet people walking in the area multiple times, especially street cleaners. After 2-3 encounters, they start waving back, wondering what this fool is doing.

🚧 The Challenges Along the Way

It’s not very rhythmic running, of course. There are many U-turns involved, and you have to keep looking at the watch a lot in order to not miss the critical turns. It will still happen, and that will require a decision on the spot: Turn around, or go for it next time? Decision fatigue can creep in that way.

Some streets are so wide, the 25 meter Node hitting rule isn’t enough to mark them completed, so I need to run those on both sidewalks. Some junctions are also huge and require a full trip around it to hit all the Nodes. Then, there are some streets which are so short and don’t feature any bends, they don’t have Nodes at all but still are named—running just the start and end Node of them will suffice, but I think that defies the purpose. Even if it’s unnecessary to run through these streets in order to increase the percentage count, I want to do it. But I’m sure I forgot a few ones this way because they just don’t show up on the map.

Some roads feature construction sites. Two options: Come back in a few months to see if they’re gone, or just hop over the fence to get to where those Nodes are. Admittedly, I always go for the latter option. Don’t do this at home, kids.

Then we have those weird streets which are marked as public but some corporation has decided to build a gate stopping the public from entering and claim them for themselves. This is a rare case here, but it happened a couple of times to me. One particular situation featured a tiny space right next to the gate where I could just squeeze through.

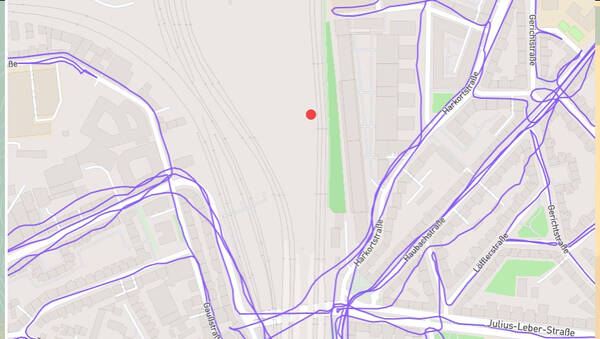

On one of my first few collecting sprees, I suddenly found myself on a road that was cars only. Trucks were suddenly speeding past me at 80 kph (50 mph), and I thought that this can’t be right and turned around. That’s how I found out about the whole OpenStreetMap editing thing.

As I said, the maps that CityStrides uses stem from the open-source mapping project OpenStreetMap, or OSM for short. CityStrides’ founder says that if a Node seems to be wrong, that the map’s fault. The map needs to be corrected, because CityStrides just pulls all the runnable streets from OSM and displays them. So I looked into this particular situation and found out that the street in question was actually marked correctly as motorroad=yes, a setting that implies foot=no. So I put on my detective hat and found a Google Doc of road types to omit inside CityStrides. In it, streets marked as highway=motorway were correctly omitted, and therefore not allowed for street collection. But motorroad=yes didn’t appear. I emailed my findings to James, the creator of CityStrides, and he was very grateful for the find and implemented it right away. Problem solved! No one needs to get run over by a truck while on the hunt for rogue Nodes.

Little challenges along the way make it all the more fun in my opinion. Compared to seeing the growing map afterwards and realizing the actual measurable progress of my actions, is a nice thing. You don’t get to see that often in other aspects of life. It feels a bit like a game to me.

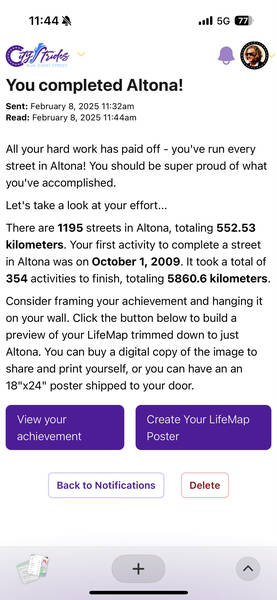

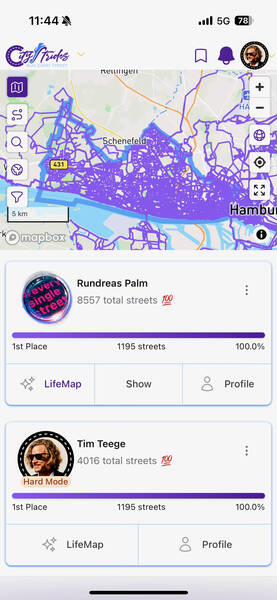

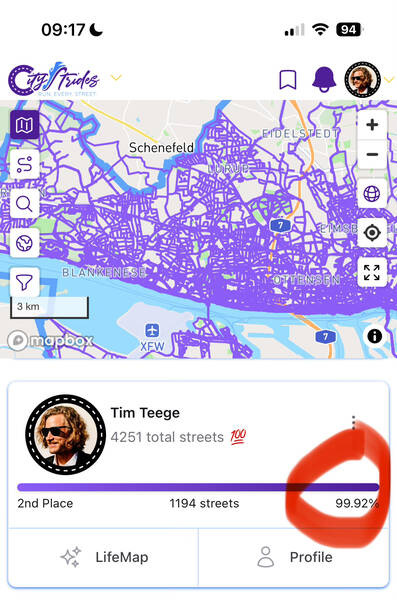

📈 My Current Personal Status

At the time of writing, I have completed two of the seven Bezirke (like boroughs) of Hamburg. Altona and Eimsbüttel. Including some progress in the remaining five ones, I’m at just under 40% of Hamburg’s total streets, 3,204 of 8,084 fully completed. This currently puts me in 12th place of around 3,000 people on CityStrides who are collecting streets in Hamburg. I was briefly in the Top 10, but the other runners sure aren’t sleeping! No one has yet cracked the full 100%, but a guy named “Rundreas Palm” is getting close with over ninety percent right now.

I don’t think chances are huge that I’ll ever reach full completion, but I like to imagine myself in my 70s, going on day-long hikes to finish some remote Volksdorf or Kirchwerder neighborhood on a sunny August day.

There certainly are worse activities!

The whole thing has massively changed my mental image of my hometown. It somehow made Hamburg simultaneously feel a lot bigger and also a lot smaller to me. And I’ve seen so many new places, all so close to where I spent so many years of my life. When getting to know a new neighborhood this way, I often like to play the game of imagining how it would be like to live in it. I have become much more open to lots of parts of my city that way. It’s been like a practical lecture in geography.

I hope to have painted a good picture of this little side quest of mine for you to understand what’s it like. Let me know what you think about it in the comments or send me an email!

How do you feel after reading this?

This helps me assess the quality of my writing and improve it.

Leave a Comment